Behind the Stethoscope: SAVE Clinic

An Epidemic

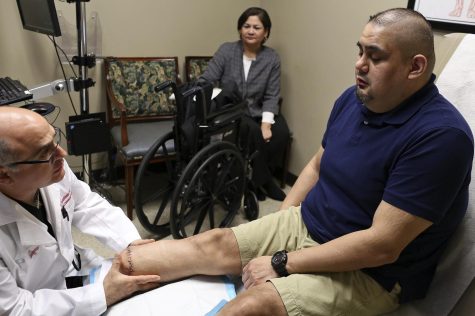

Chatter erupts and floods the hall as doctors, physician assistants, and medical assistants cram into the patient exam room. Inside, an elderly man sits on his wheelchair as Dr. Ochoa uses an iPhone to take pictures and document an uncontrolled infection eating away at the bottom of his foot. His other leg was amputated due to a similar situation, and now he is in great danger of losing his last leg. Rising above the dissonance of talking, his daughter’s voice conveys raw pain, disappointment, and fear as she explains to Dr. Ochoa how she tried to be the best caretaker for her father and that the family has prepared for the worst scenario of amputation. As I leave the crowded and frantic room, I hear a physician assistant calmly comfort the man in Spanish: “Don’t worry, we are all going to take care of you.”

This is a common scene at San Antonio Vascular and Endovascular (SAVE) Clinic, located in the Southside of San Antonio. The clinic is on the frontlines of an epidemic that has been affecting underprivileged San Antonio communities for generations. San Antonio has some of the highest incidences of diabetes-related lower-limb amputations in the nation, affecting over 2,000 residents each year.

Many of them are not diagnosed with diabetes until an end-stage complication appears, such as a diabetic foot ulcer. At that point, their diabetes has been uncontrolled for years, sometimes decades, creating permanent damage. High blood sugar from diabetes can damage nerves and cause neuropathy where they lose feeling in their feet, so it is easy for them to get a cut and never notice it. In a healthy person, the immune system should fight off any resulting infection. However, in a diabetic, an infection may continue to spread through the bone and up the legs because diabetes attacks the small blood vessels in the feet, reducing blood flow carrying immune cells to the infection site. An insignificant cut for most can become a life-threatening infection for diabetics that may warrant amputation to prevent it spreading to the rest of the body.

These end-stage complications can be avoided with proper management of diabetes and a healthy lifestyle. So then why are there so many people in San Antonio, even in their 30s and 40s, suffering from this completely preventable condition? The answer lies partially in a health system that does not adequately serve underprivileged, mostly Hispanic areas of San Antonio. For many in these communities, such as in the Southside, healthcare accessibility is poor because they are uninsured and cannot pay, have to take off work and sacrifice income to seek care, or lack the transportation to reach care. Additionally, health literacy is low in these communities because of lack of education and generations of severe health issues, such as heart attack, stroke, and amputation, which all contribute to a false perception that these health outcomes are “normal” and out of their control.

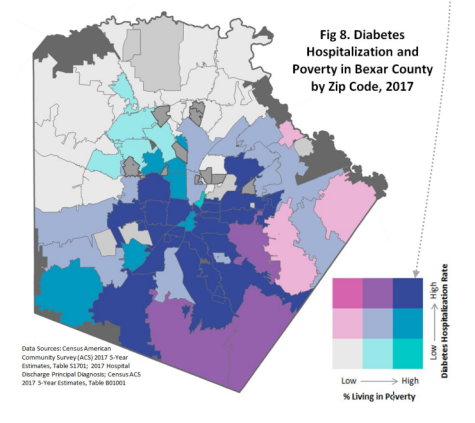

The health disparities between affluent and underprivileged neighborhoods are stark. Certain zip codes in the South and West sides have lower-limb amputation rates three times higher than the average rate in Texas, a grotesque stamp of past policies deliberately designed to segregate the city by race and class. The same neighborhoods that were redlined in the 1930s by the federal government to discourage investment in communities of color are the same neighborhoods that experience high rates of diabetes-related amputation today. The strongest predictor of health is not behavior, medical care, or even genetics—it is someone’s zip code.

The Heroes

Walking through the hallway filled with evocative paintings of John Lewis and Ruth Bader Ginsburg, it doesn’t take long to realize that SAVE Clinic is on a greater mission, continuing their fight for equality in America. For SAVE Clinic, that means fighting for health equity in San Antonio. Dr. Lyssa Ochoa, a vascular surgeon from the Rio Grande Valley, founded the clinic in 2018 to reduce diabetes-related amputations. She recognized that her clinic must be located in areas with the most need, and that is exactly what she did, making SAVE Clinic one of the only specialty care clinics located in the Southside, where the patient population is the poorest and sickest.

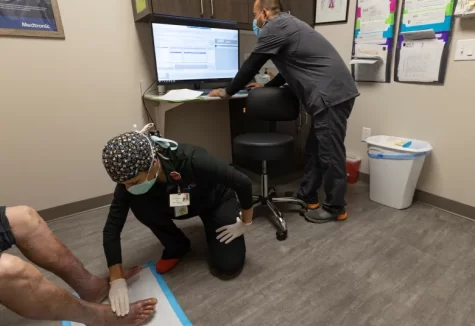

The team at SAVE Clinic focuses on providing patients with the best health outcomes possible, but they know that to do this, they must address the social determinants of health. Medicine does not occur in a bubble. To reduce the transportation barriers for the many low-income patients who do not own a private vehicle, the clinic goes to them, traveling to seven satellite clinic locations in underserved or rural areas. The simplicity of this solution is deceiving as the time, expense, effort, and logistics necessary to pull off such a feat is impressive. On travel days, the team of medical assistants, ultrasound technicians, and physician assistants loads up a 15-passenger van with ultrasounds, computers, and all the equipment they need to set up their stations and diagnose patients. The extra work is worth it because, as Dr. Ochoa explains, “Bringing the clinic to the patients is much easier than having the patients struggle to reach the clinic.”

You can tell that the team members genuinely care for the patient and want to do everything they can to set them up for success, whether that means handing out pamphlets to improve health literacy on diabetes or working with an uninsured patient to figure out a health insurance plan that works for them. The surgeons sometimes even arrange for transportation to and from the hospital if a patient does not have someone in their support system available to help.

In most medical practices, patients are expected to navigate the complicated healthcare system on their own. For example, doctors may tell patients to get an MRI before their visit so that they can figure out a course of treatment, but there are a number of hurdles patients must jump through to complete this: who do I call, what hospital do I go to, will my insurance pay for it, how do I get transportation, and who can I get to take care of me after? Instead of adding to the burden of their patients who are already dealing with difficult life circumstances and the trauma of sickness, SAVE Clinic alleviates this burden as much as they can. Their actions boil down to a single question: How can I help?

To meet their patients’ needs, the clinic draws upon a collaborative network of other doctors, hospitals, academic centers, city councils, county commissioners, and nonprofits to coordinate patient care quickly. You do not have to look for long to see Dr. Ochoa or her clinical partner Dr. Gianis on their company iPhones, text messaging other doctors or hospitals to figure out treatment plans or schedule patients for surgery. This direct communication enables them to better understand their patients’ ailments and treat them quicker. I have even watched as Dr. Gianis assessed a patient, realized the patient needed an angioplasty, texted the scheduling team, and scheduled his patient to get the procedure at their outpatient surgery center the very next day—all within 15 minutes.

A Path Forward

Dr. Ochoa and the SAVE team have worked tirelessly and passionately to provide the best care for their patients suffering from vascular disease. However, the more difficult goal they work towards is preventing people from even developing these end-stage complications and needing to see them. SAVE Clinic cannot do this alone. This requires the efforts of the entire community to not only change the healthcare system, but also the systems that maintain the status quo of poverty and poor social determinants of health for the low-income, Hispanic communities that make San Antonio the rich cultural city it is. “If we can’t keep half of San Antonio healthy, there’s no way our city can prosper,” says Dr. Ochoa. ”

She made integrating SAVE Clinic into the community a core part of its mission because she believes that to even begin making strides in improving the health of the community, they must earn the trust of the community they serve—a difficult task considering these people have been abandoned and ignored by public institutions for generations. This trust is built by showing up for their community and letting the people know that they genuinely care. They do this through various community engagements, including lectures for community centers and seniors, attending health fairs, and doing free health screenings. The process of trust-building may take years, or even decades, but the fruits of these efforts will yield exponentially healthier communities in San Antonio.

When I shadowed Dr. Ochoa and Dr. Gianis, I was confronted with the grim reality of health in San Antonio. Most of the patients that walked through those clinic doors with diabetic foot ulcers or amputations did not have much longer to live. The damage had already been done by years of uncontrolled diabetes, poor diet, sedentary lifestyle, and most of all, neglect by the wider San Antonio community. But, seeing the compassion and care of everyone who worked at SAVE, from the nurses to the receptionists, gave me hope. Hope for a future in which people do not die of complications from a completely preventable disease. Hope for a future in which people are empowered to care for themselves and the people around them. Hope for a future in which a child, no matter what part of the city they are from, can expect a long and happy life instead of hoping for one. SAVE Clinic is leading the way towards this future. The question we have to ask ourselves is: how can I help?

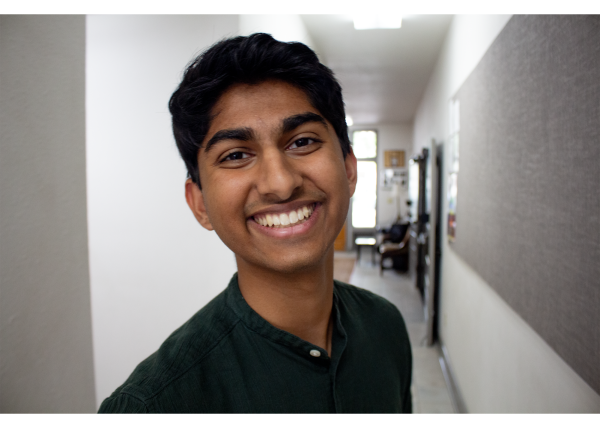

Niraj is a current Senior at Keystone who is interested in spreading awareness about health issues and inequality through his writing. He is fascinated...

Mindy Taylor • Feb 23, 2023 at 5:42 am

Beautifully Written! How can I help?