Neil and Antonin: the Hulking Beasts to Never Meet

In 1983, faithful reading of the constitution died at the age of 183 years by the appointment of one Antonin Scalia. In 2016, Scalia died at the age of 79 years by a heart attack. In 2017, the former’s grave was buried 10-feet deeper by the appointment of Neil Gorsuch. For what had seemed to be a blow to originalism and the herd of Federalist Society members it carried with it, now seems to be a kiss of death upon the grave of jurisprudence.

For all that he was, Scalia was an excellent legal theorist, penning dissents to liberal court-rulings with a fiery tact. Whilst deciding Obergefell v. Hodges, he stated the “American people had lost the most important liberty they asserted in the Declaration of Independence and won in the Revolution of 1776: the freedom to govern themselves…”. Within Heller v. District of Columbia, Scalia flooded the Court opinion with expertly integrated quotations describing the historical lineage of thought on the Second Amendment. However, his expertise, in theory, is not to suggest that his motivation is at all nonpartisan. Much rather, he uses these legal building blocks to stack a monolithic machine for conservative judgment. Through this Scalia-thought-machine, basic tenets such as freedom of religion went through the cogs until they somehow turned into a Christian-preferential judgment to religion-related freedom of speech in his Lee v. Weisman dissent.

For all that he was, Scalia was an excellent legal theorist, penning dissents to liberal court-rulings with a fiery tact. Whilst deciding Obergefell v. Hodges, he stated the “American people had lost the most important liberty they asserted in the Declaration of Independence and won in the Revolution of 1776: the freedom to govern themselves…”. Within Heller v. District of Columbia, Scalia flooded the Court opinion with expertly integrated quotations describing the historical lineage of thought on the Second Amendment. However, his expertise, in theory, is not to suggest that his motivation is at all nonpartisan. Much rather, he uses these legal building blocks to stack a monolithic machine for conservative judgment. Through this Scalia-thought-machine, basic tenets such as freedom of religion went through the cogs until they somehow turned into a Christian-preferential judgment to religion-related freedom of speech in his Lee v. Weisman dissent.

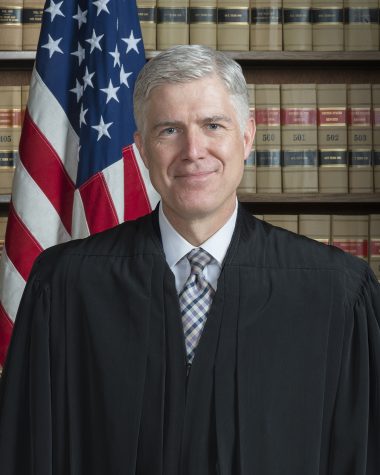

Associate Justice Neil M. Gorsuch; photograph by Franz Jantzen, 2017.

Gorsuch’s knock-off brand thought-machine serves the same purpose but does not retain the bells and whistles of the tried and true Scalia-machine. However, originalism is now no longer the dissenting opinion. Thanks in part to Gorsuch’s vote, a 40-foot cross was allowed to stand on public property, and that’s merely the beginning; on Chevron v. Natural Resource Defense Council, Inc., a case that rightfully limits judicial power on making judgments on governmental agencies, Gorsuch has stated bluntly that “[w]e managed to live with the administrative state before Chevron. We could do it again.” Unfortunately, Gorsuch seems to have glossed over that, if combined with recent activism within the court on the fault of Scalia and his successors, Chevron deference seems to be the only way to subset the powers of the judiciary in making decisions on behalf of the executive branch. Simply put, Gorsuch is not arguing an originalist viewpoint against Chevron for the sake of upholding institutions of the past, but, rather, arguing against Chevron to capitalize on the new right-wing rise in the Supreme Court. Without Chevron, the power of judicial review would not be to simply uphold and interpret the law but to also command how the law will be executed. Without Chevron, Gorsuch gets his way not only on rulings for the foreseeable future but also gets his way on how fundamentally the American government acts.

Seeing as the court is rapidly becoming a menagerie of party animals, it seems fitting that Scalia is a large, hulking elephant. With every court case he took up came a monstrous crater where his footing had been. Then comes Neil, who traipses the path set before him rather clumsily. At the spry age of 52, who knows how far he can go. Most likely much farther than the slow and steady Scalia.

Much farther, much too fast.

Jack Dougherty is a senior at Keystone who enjoys participating in Model UN and Academic Worldquest and has lately found himself in the midst of helping...