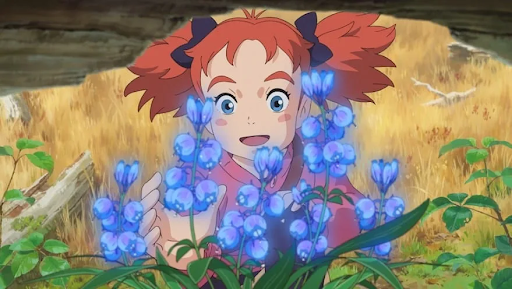

Studio Ponoc, an offshoot of the internationally acclaimed Studio Ghibli, released Mary and the Witch’s Flower, a coming-of-age animation directed by Hiromasa Yonebayashi, in 2017. The story follows Mary, a clumsy young girl living with her grand-aunt, whose good-hearted intentions always end up in disaster. Overcome by boredom, she is led into a forest by two playful cats where she finds a glowing purple flower. Fascinated by its beauty, she takes the flower home to inquire about it with the resident gardener. Mary’s choices lead to a catastrophic force unleashing itself in the forest and taking hostage one of the cats. In search of the lost cat, Mary discovers a broomstick which, with the newly discovered magic of the flower she found in the forest, takes her to a peculiar island. Her search for the missing cat leads her to discover the repercussions of her naivety and power in the wrong hands.

Delineated as an amenable and curious young girl, Mary is the epitome of the “innocent child” archetype. Telling the story from Mary’s perspective enables the improbable to become probable. That is to say, the validity of her point of view is questionable. Yonebayashi deliberately confines the story’s perspective to that of children and the elderly to limit the extent to which adult “rationality” can be applied to the situation. Moreover, the only adults that appear in the story are the antagonists, who are corrupted with greed for power despite being aware of the consequences.

These rhetorical choices contribute to the story’s contention that being someone of importance isn’t defined by power, but rather by one’s disposition and choices. Those in the story who actively seek out power despite the inadvertent risk of catastrophe continuously fail because they ignore their inherent duties as peacekeepers in society. Mary is no exception from this phenomenon; when Mary first discovers the power the flower gives her, she relishes in the praise she receives, becoming blind to the situation at stake. It’s not until she jeopardizes the safety of her friend that she realizes that she is mistaken about her priorities. It’s this revelation that teaches her that she doesn’t need magic to feel confident in herself. By going through life-altering experiences where all that she cares for is at stake, Mary learns the importance of prioritizing her humanity over self-indulgence.

Although Mary ultimately loses the powers the flower granted her, she changes a lot by the end of the story. She maintains her eagerness to help others, but she no longer feels as insecure about her clumsiness and stubbornness; rather, she sees these qualities as strengths. Ultimately, Mary is still the same naive and innocent young girl she was in the beginning, only more self-assured, a critical asset to have in her pursuit of happiness.

Although I can’t say for certain Yonebayashi intended this, I believe this animation is a message to those nearing adulthood. During this transitional phase in life, there is pressure to be independent, self-reliant, and make a name for oneself. All of this culminated, it’s inevitable to make mistakes or lose oneself in the process. This animation, which serves to remind us of the simplicity and inherent good of human nature, conveys the general truth that it’s not our conspicuous attributes that define success, but rather our genuine character.