On December 6, 2023 (a school day, mind you), I went to see the USA release of the latest film by Studio Ghibli, The Boy and the Heron. I had been awaiting the moment for years at that point, since it takes a truly long time for a handful of animators to produce two hours of (mostly) meticulously hand-drawn frames.

So I was then quite confused when the film was not as endearing to me as the other works of Studio Ghibli, especially compared to those by the same director, Hayao Miyazaki. It seemed to me while watching the movie that I was missing something, so I went and watched again, then once more after that. Still, I was not satisfied.

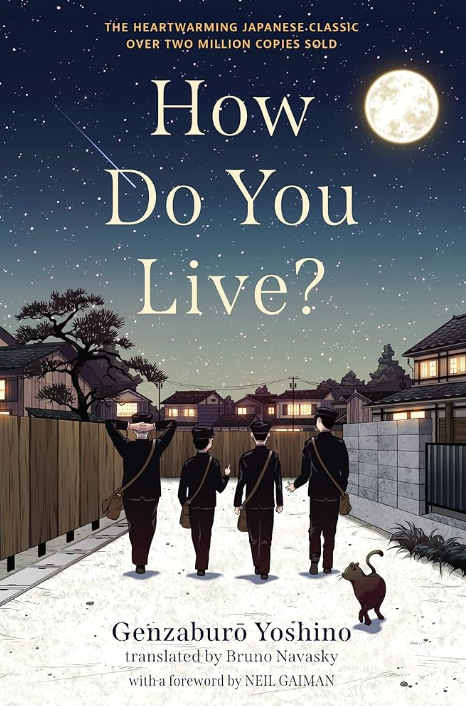

Months later, on the travel society trip to Europe, I found a book titled How Do You Live? by Genzaburō Yoshino in a bookstore in Berlin. The book, I knew, was at least in some way an inspiration for The Boy and the Heron. In fact, it is the namesake for the original Japanese version of the film. Why they changed it from such an interesting title, I am not sure.

I purchased the book and quickly began reading it, hoping to find some clues to help me understand the film I so wanted to enjoy. I also wanted a more leisurely and abstract book before exploring the very real issues described in our required summer reading book, Just Mercy. As it turned out, this book only left me with more questions to consider and ideas to ponder over.

The chapters of the book alternate point-of-views: one is through the narrator’s eyes, a boy nicknamed Copper after Copernicus; the other is entries from a notebook Copper’s uncle keeps, journaling his noticings of Copper’s developments and how he thinks, which he plans one day to gift to him.

I recall reading the first scene before falling asleep in my Warsaw hotel room which has stuck with me months later and will continue to do so. Copper and his uncle are on a rooftop, observing the bustling people of Tokyo below. As they watch, Copper realizes that as he was down there on the streets earlier, there very well could have been another person peering down on him. He then experiences a strange feeling, realizing that the world doesn’t revolve around any one person. From there, he provides a wonderful analogy: people are like molecules in the tide of humanity. It was this universality the book offers, following a regular boy who seems so special in his way of thinking, that I really love.

The book continues in a similar fashion, with Copper trying to learn more about the world around him through his curiosity in both scientific and social matters. After each anecdote Copper gives, his uncle’s entry explains a lesson to be learned. It is truly inspiring and can very easily change one’s view on the world, living up to the expectations given by the back of the book that compare it to The Alchemist and The Little Prince.

Towards the end, however, it takes a turn, and powerfully conveys Copper’s guilt and regret. In his case, such feelings are caused by a simple slip-up, though it haunts him for many weeks. What makes this passage special is that the reader is not thinking about Copper’s situation, but rather their own, revisiting past regrets and determining how to relieve guilt associated with them.

It’s possible that the reason Miyazaki named his movie after How Do You live?. It is clear that it is in multiple ways a reflection of Miyazaki’s own life, especially since the movie was produced to be his last. The plots of the two works are not remotely similar; neither are the themes at first glance. However, I am sure that in Miyazaki’s mind they occupy a very close space where the emotions inflicted by the book directly influenced his vision for the movie.