On Leaving

Reflections of an Outgoing Senior

I’ve always been leaving San Antonio. Been a tightly packed overnight bag, a locked rolodex, a warm winter coat hanging in-reserve by the doorway. Been a full tank of gas — or at least enough to reach the city limits. I’ve been a clock wound to Pacific Standard and to Eastern Daylight. Been a coastal haze and a desert breeze. I’ve been the bustle of midtown at midday and dawn along Highway 1. I’ve been a midnight road trip, a foggy rear view mirror, a smudged return address. Been a future without a present, a there without a here. I’ve always been leaving San Antonio.

Home — it’s been an idea — a vast array of conditions to a singular end: to go, to rev and to race and to never return. So I found solace in the sprint. I sought peace running circuits in the graphite-stained 2-AM lanes of my mind — in hand cramps and calculator taps and chapter headers. And my home lay somewhere — somewhere in the inky, tangled conjugation of the integral of the thesis of a road stretching out and away.

I listed while I ran. The days I kicked into darkness, gaze fixed on the glow of a tungsten desk lamp. Vocabulary. GPA tallies. SAT practice scores. All the Lorenzos I could’ve been — all the lives I could’ve lived on different roads, in different lights. The nameless years I left doggie-eared and annotated and taped shut, strewn on the pavement behind me. The invites declined, the photos unshot. I listed leashed laughter, stayed smiles, all the unuttered “yeses” that slunk on the curb in my shadow. I listed while I ran, but didn’t understand. Didn’t pause for “first prom” or “class president” or “pandemic.”

And my road grew smaller, denser. My leaded pavement, my red-pen veins, my college-ruled slumber. My world became one lane, one dimension. It was the central corridor of North Hall at midnight. And my skull was drop-ceiling, and my socks were gray carpet tile. But I kept running. I ran because it’s what Keystone students have always done. We outran Sputnik and bankruptcy and fire. And I ran because my father ran — dashed in the mower rows Abuelito traced on his high school field. I ran because my mother showed me to stay hungry, to sweat, to fight. I ran because my Mane Lilia taught me to bear a burden.

Bend. Step. Breathe.

I got there — to the end of the line. Got the big white envelope, the confetti. I got the tears and the hugs. I got the jumping and the cap and gown and the “I knew you had it in yous.”

But then what?

So I suppose I’m leaving San Antonio. But hadn’t I always been leaving? Hadn’t I just spent a decade running? Years on the road out of town? And then it struck me: Dear Lord, I’m leaving San Antonio. All the while, all the numberless seasons I passed in motion, I had stumbled into home — not the abstraction I devised in my mind. Not the home with the radical roof, the modulus mortar, the bell curve brick. Not the home on the straight black road that wound in itself into nothing. True home — it found me while I was most blind. Home was a sound. Home was the call of the mourning dove in early spring and the tuning of cicadas in late September. It was the jazz my mother left idle on the radio during dinner. It was the muffled “do-re-mi” wafting from Mrs. Hensley’s second-story window. It was Penny’s mischievous chuckle, the wheezing of pier and beam floorboards. The audience chatter before curtain call, the 5-o’clock bugle, Mr. Al’s “move up.”

Home was a touch. A pat on the back, the sear of a joyful Sun at noon. It was a teammate’s clasped hand and the “Cheesegrater” and a fifty-layer lacquer coat on the Stevens’ Hall banister. Home was a spider web, a concrete constellation that tethered lost teeth and scraped knees, crayon wax and Chopsticks. Home where I took my first breath and first step. Home where I shed my first tear and made my first friend. Home where Abuelo’s snoring still clings to the stucco walls like cigar smoke. Home was that fresh-baked-honey-butter-biscuit embrace, the invisible arms wrapped around me that said, “it’s okay to run. But remember.”

Remember who put you here. Remember their eyes and their dreams and their love. Remember breakfast tacos and Magic Treehouse. Remember who you used to be — the garrulous kindergartener and the performer and the skeptic and the clown.

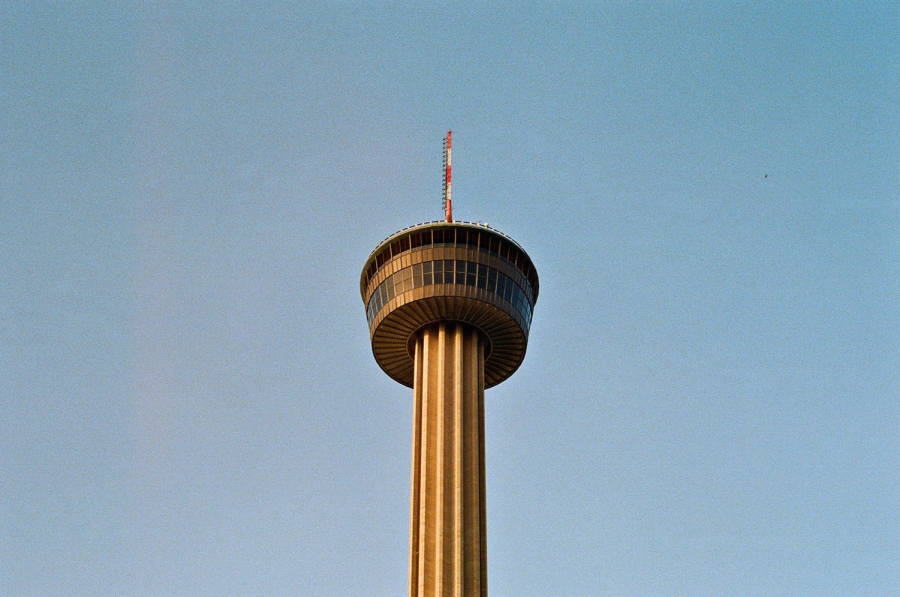

To remember is to affirm your own humanity. It’s to accept that your character is but a roughly molded sculpture of a thousand hands. And you run not despite your past, but for it. And you’re a rainy Tuesday and a red acrylic cup with apple juice, you’re an afternoon Caraway lecture and a pipe cleaner butterfly and a torn up blacktop, you’re a big small town with short beige towers and a narrow brackish river. You’re HemisFair ‘68 and pop eggs and borderless summers. So go on, keep running. Run for the state line, run for the coast. But remember, remember home.

In the twilight months of high school, I’ve taken to slowing down. Yes, I still study too much — but I’ve started to reflect more. I’ve tried to make up for lost time as it were. I’m breathing and seeing and feeling. I’m remembering, remembering the memories I should’ve made.

Somewhere along the road — maybe a mile before lockdown — I missed learning to drive. Too busy to bother I suppose. Too deeply buried below mounds of flashcards and binders and Bic mechanical pencils. But I’m driving now. I have a “real legal human adult license for motor vehicles” as I like to call it — people still don’t believe I got one, some three years too late. Highway driving — though that still frightened me. When surface roads exist, why put yourself at risk? Those speeds? No thanks.

My father says I should get comfortable with it before going off to college. Last Sunday evening — one of those spring evenings that splays out toward infinity — he jingled the keys and hauled me to the driver’s seat of our SUV. I started the engine, pulled out of the driveway, traced the avenues of my childhood. Past the long-dead neighbor’s fence, past the shuttered Kitty Park, past the H-E-B and the tree-shaped bus stop. And past all the trick-or-treaters and the multicolored Christmas lights and the birthday banners and the storm clouds and the dawns. I merged with 281 heading North. And past the ice cream shop and the smokestacks and the movie theater Saturdays with Grandma. Past the snow and cascarón confetti and I was driving. Driving sixty five down the wide white road up and away.

“Don’t forget to check your rearview mirror,” my father reminded me.

The San Antonio skyline in reverse. I’d never seen it that way.

Lorenzo Ruiz, a senior, is a Coeditor-in-Chief. An enthusiast of government and current events, his hobbies include debate, Academic WorldQuest, Model...