The Elusive Statehood of Puerto Rico

Introduction

We’ve all seen headlines on the Internet, read articles in the paper, or heard speeches delivered by political pundits and elected officials alike––pseudo-prophetically forecasting the rapidly approaching addition or rejection of a fifty-first state to the union. Hundreds of articles from the past decade boast headlines to the tune of “The 51st State” and “Designing a 51-State Flag,” yet very little has changed since their publication (both examples in 2012, following a conclusive pro-state referendum in Puerto Rico). A path to statehood for P.R. has been debated on the national stage since the 1940s, and henceforth, it’s seen enthusiastic support by Republicans and Democrats alike. From Ronald Reagan to Barack Obama, the advancement of the territory’s status has, at least in-word, been a rare subject of agreement amongst politicians and their party platforms. So, we’re faced with a critical, somewhat baffling question: why hasn’t the state—seemingly everyone wants—come to fruition after eighty years of debate and development?

A Microcosm

From a mainland perspective, we have a reductive tendency to view Puerto Rico as an ideological monolith, a caricature condensed to a single issue (statehood) with a unified front in its favor. And why shouldn’t we? Chances are most coverage of the topic you’ll encounter centers on the rift between federal and local will. In reality, Puerto Rico, just like any democratic jurisdiction, is a diverse collage of political beliefs unto itself—a fact often overlooked for the sake of simplicity.

At the heart of the argument surrounding Puerto Rico’s continued relationship with the United States are two regional political parties: the Popular Democratic Party (favoring existing Commonwealth status) and the New Progressive Party (favoring statehood). In recent decades, both regional parties have used their opposing positions on status to galvanize popular support, and on the majority of social and economic issues, it’s fairly appropriate to conflate the former with the mainland Democratic party and the latter with “traditional,” center-right Republicanism. Where things become complicated, however, is the linchpin topic of statehood.

Somewhere along the roughly 2,500-kilometer span between San Juan, Puerto Rico, and D.C., center-left views on commonwealth status grew ambiguous. While the DNC party platform broadly states “[t]he people of Puerto Rico deserve self-determination on the issue of status,” general progressive consensus in the territory explicitly favors retention of commonwealth status. So, what underlies this massive disconnect, both between the federal-territorial levels of government and amongst the island’s ~3.2 million inhabitants?

Why Not?

As any good historian will advise: in the course of tracing a historical development, start with the money and work from there. In the case of P.R. statehood, economics is a keystone concern. Operation Bootstrap, a 1950s federal government initiative geared toward industrializing the island’s economy, sparked a decades-long stretch of rapid economic growth which reached full force during the late-70s. Puerto Rico’s unique position as a “commonwealth” territory opened up the island to a variety of industry-supportive economic policies. Section (§) 936, passed by Congress in 1976, granted massive tax incentives to corporations sourcing revenue from and basing subsidiary corporations in U.S. territories (namely Puerto Rico). Despite remaining relatively poor in comparison to the rest of the United States, the island’s economic condition steadily improved through the 80s and early-90s as a result of heavy investment from mainland commercial interests.

It’s this trend that spurred on a sizable chunk of popular support for commonwealth status—many Puerto Ricans embracing territorial limbo as a federally-fueled engine for improving living conditions and a beacon of investment from wealthy companies.

However, the catalytic effects of § 936 came to an end in 1996 when President Clinton, following mounting mainland opposition to Puerto Rico’s perceived role as a tax shelter for the ultra-rich, began a ten-year-long repeal process.

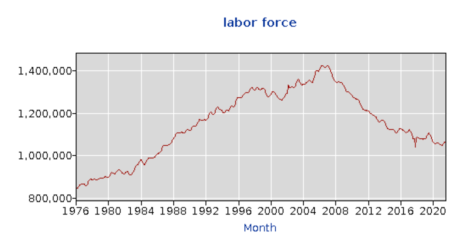

Almost immediately after termination, the territory’s economy was sent into a dire tailspin from which it has yet to recover in the slightest. Exacerbated by the Great Recession of 2008, Puerto Rico has seen a shrinking labor force and rising debt. Today, the former stands at just 75% over December of 2006 with no signs of improvement, while the island’s debt totals about 71 billion dollars.

With hefty tax incentives largely out of the picture, how else do supporters of commonwealth status justify their position? For many on the center-left, territorial designation remains more a matter of national pride than of tangible political or economic benefit. After nearly seventy years of official self-government and centuries of cultivating a distinct identity, the prospect of further integration alongside the Union’s existing fifty states is challenging for many residents on the center-left.

Pushing for Statehood

For eight of the past twelve years, gubernatorial power has been concentrated in the hands of the pro-statehood New Progressive Party, with federal-level party allegiance varying between Republicans and Democrats. Referendums concerning statehood have been held under each of the past three NPP governors (in 2012 under Gov. Fortuño, in 2017 under Gov. Nevares, and most recently in 2020 under Gov. Vázquez). The first resulted in a request for statehood which was eventually shot down in committee and the second came up “inconclusive.”

The most recent plebiscite, held in November of last year, posed a simple “yes” or “no” question to voters: “Should Puerto Rico be admitted immediately into the Union as a State?” 52.52% of voters sided with the affirmative. Thus, the issue of statehood is largely passed on to the national level of government for debate, approval, or rejection. This brings us back to the domain of standard party politics.

Losing Footing

Two years into his first term, President Reagan outlined the following attitude on status: “While I believe the Congress and the people of this country would welcome Puerto Rican statehood, this administration will accept whatever choice is made by a majority of the island’s population.” Official Republican platform aligns with this stance, too: “We support the right of the United States citizens of Puerto Rico to be admitted to the Union as a fully sovereign state.” This does, of course, come on the heels of two conclusively pro-statehood referendums on the island (i.e. self-determined status).

When it comes time for Congress to act decisively in the face of a formal request for statehood, however, the platform takes a back seat in the minds of Republican leadership.

Just over a year ago, then-Senate-Majority-Leader Mitch McConnell said, “[a]fter they change the filibuster, they’re going to admit the District as a state. They’re going to admit Puerto Rico as a state. That’s four new Democratic senators in perpetuity,” concerning mainland progressive interest in statehood.

Just over a year ago, then-Senate-Majority-Leader Mitch McConnell said, “[a]fter they change the filibuster, they’re going to admit the District as a state. They’re going to admit Puerto Rico as a state. That’s four new Democratic senators in perpetuity,” concerning mainland progressive interest in statehood.

In recent years, political opinion on the subject has grown increasingly polarized. Some conservatives claim, in opposition to the official GOP position, that Puerto Rican statehood would be disastrous for their party’s continued success—and, thus, something to be avoided at all costs. Once more, mainland politics condenses the national political outlook of Puerto Rico to a liberal monolith set on confirming Democratic Party dominance on the national level.

“I think there’s a disconnect to a great degree as to what some people [who] belong to one of the national parties in Puerto Rico feel they want to support and what their counterparts in the mainland support,” expressed Gov. Luis Fortuño, a pro-statehood Republican and NPP member, in conversation last September.

“The issue is that there are competing interests in Washington all the time and the problem here is that, if you have your two senators and Congressional delegation fighting for you, your fight is easier. Whereas, if you don’t have any senators and you only have one non-voting member of Congress, it’s like going into a ring for a fight with one arm tied behind your back.”

Today and Tomorrow

Just as Republican support for statehood wanes, many progressive Democrats have shifted toward broadly fighting for self-determination as opposed to explicitly favoring statehood. With plebiscites conclusively favoring the latter, the distinction might seem insignificant—but in the halls of Congress, it’s certainly not.

At the moment, there are two competing bills on Capitol Hill: both a response to Puerto Rico’s push for statehood and both tackling the issue of future status. S.780 (Puerto Rico Statehood Admission Act) draws center-left support and specifically pushes for statehood, while sponsorship for S.865 (Puerto Rico Self-Determination Act of 2021) is concentrated amongst progressive Democrats (e.g. Bernie Sanders, Elizabeth Warren) and calls for a new referendum on status with greater federal involvement.

Division within the Democratic party isn’t an encouraging indicator of how these bills will progress over the coming months, and an unfortunate reflection of gridlock, polarization, and partisanship that’s plagued one island’s quest for political identity.

Division within the Democratic party isn’t an encouraging indicator of how these bills will progress over the coming months, and an unfortunate reflection of gridlock, polarization, and partisanship that’s plagued one island’s quest for political identity.

With an ever-weakening economy, shrinking population, and enduring infrastructural and moral damage, statehood remains for many U.S. citizens in Puerto Rico—not merely an endeavor of place—but of survival. Now, it’s up to Congress, for whatever that’s worth.

Lorenzo Ruiz, a senior, is a Coeditor-in-Chief. An enthusiast of government and current events, his hobbies include debate, Academic WorldQuest, Model...