Together, We Can Eradicate Female Genital Mutilation

Zero Tolerance for Female Genital Mutilation. Stop female genital mutilation. Zero tolerance for FGM. Stop female circumcision, female cutting stock illustration

Sensitive content warning: mentions of blood and reproductive systems. Continue at your own discretion.

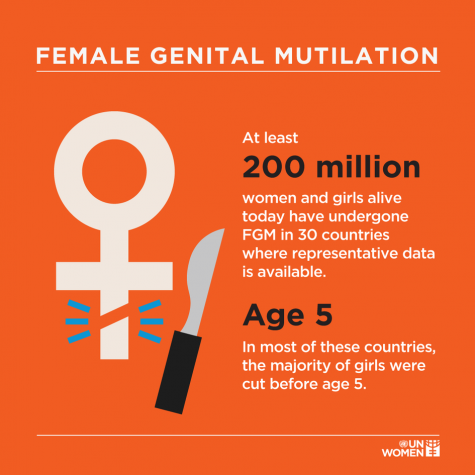

Sweat clings to the little Sudanese girl as she walks home from school. Upon arrival, her aunt leads her to one of the small rooms at the back of the house. Naked and exposed, the little Sudanese girl was made to lay atop a table. “You are not closed enough,” her aunt declared. The little Sudanese girl kicked and screamed as she was brought to the midwife. The girl’s genitals were cut — she bled, she swole, she hurt, she wanted to die. Years later, her doctor told her that, due to her infibulation, she could never have children. It is estimated that two-hundred million girls alive today have undergone female genital mutilation (FGM), often performed for the sake of preserving female virginity and chastity, with three million more women and girls at risk every single year.

In 2003, the United Nations (UN) declared February 6th the International Day of Zero Tolerance for Female Genital Mutilation. This day was established to promote the awareness of a movement that calls for the rights of the bodies of women and girls around the world.

To begin, FGM is the ritual cutting or removal of some or all external female genitalia for non-medical reasons. There are four main types of FGM — (1) Clitoridectimy: removal of the clitoris; (2) Excision: removal of the clitoris and the labia; (3) Infibulation: a narrowing of the vaginal opening, sometimes through stitching; and (4) all other harmful procedures not covered by the first three: including pricking, stretching, scraping, or the use of acid to mutilate parts of the genitalia. Girls who undergo FGM are cut at a young age, often before the girl’s fifteenth birthday. FGM is undergone, not for health benefits, but for the preservation of the woman or girl’s virginity, marriageability, and for the enhancement of male pleasure during intercourse. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), FGM results in a variety of health complications including severe bleeding, difficulty with urination, menstrual issues, childbirth complications with a higher probability of newborn deaths, and increased risk of cysts and infections which can ultimately lead to the woman’s death.

To begin, FGM is the ritual cutting or removal of some or all external female genitalia for non-medical reasons. There are four main types of FGM — (1) Clitoridectimy: removal of the clitoris; (2) Excision: removal of the clitoris and the labia; (3) Infibulation: a narrowing of the vaginal opening, sometimes through stitching; and (4) all other harmful procedures not covered by the first three: including pricking, stretching, scraping, or the use of acid to mutilate parts of the genitalia. Girls who undergo FGM are cut at a young age, often before the girl’s fifteenth birthday. FGM is undergone, not for health benefits, but for the preservation of the woman or girl’s virginity, marriageability, and for the enhancement of male pleasure during intercourse. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), FGM results in a variety of health complications including severe bleeding, difficulty with urination, menstrual issues, childbirth complications with a higher probability of newborn deaths, and increased risk of cysts and infections which can ultimately lead to the woman’s death.

Every Woman, Every Child, a global movement, writes that “[a]lthough primarily concentrated in 29 countries in Africa and the Middle East, FGM is a universal problem and is also practiced in some countries in Asia and Latin America. FGM continues to persist amongst immigrant populations living in Western Europe, North America, Australia and New Zealand.” In addition, the number of women and girls experiencing FGM has increased rapidly due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) estimates that pandemic-related school closures and disruption to aid-programs mean that a further two million girls face the risk of FGM in regions where the practice is prevalent. Rising poverty due to the pandemic has also contributed to the rise of FGM as there is often a correlation between FGM and child marriages, with FGM seen as raising the girl’s value in marriageability. In order for the families to survive the increasing level of poverty, they often send their daughters to undergo FGM as a precursor to child marriage, from which they receive a dowry. Additionally, 600,000 women and girls living in Europe have undergone FGM — according to Anna Widegren, director of the End FGM European Network, “[b]ecause the girls don’t necessarily go to schools right now, there are closures, there is more time for healing so it’s less a chance of being detected by either health services or educational partners.”

The UN had aimed to eradicate the practice of FGM by 2030. However, even before the pandemic had struck, this goal had seemed highly unlikely. Only 0.12% of humanitarian funds go towards combating gender-based violence, and the UN estimates that $2.4 billion is needed over the next decade to eradicate this practice. However, due to increased awareness and lower toleration for this harmful practice within the younger generations, the future seems to hold hope. There are three main ways we can actively try to put an end to FGM today — (1) Education: teaching teachers and doctors what signs to look for and how to respond appropriately to these signs; (2) Cultural Intervention: survivors telling their stories to their own community; and (3) The Creation of Laws and Policies: enforcing consequences when FGM is carried out and making policy changes that further deter the practice.

Although February 6th is the International Day of Zero Tolerance for Female Genital Mutilation, the world must use every day as a starting point to eradicate this harmful practice and preserve the health of the bodies of women and girls around the globe. As global citizens, we have the responsibility to uplift those afflicted with suffering and create a better life for people like the little Sudanese girl.

Sources

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/International_Day_of_Zero_Tolerance_for_Female_Genital_Mutilation#:~:text=International%20Day%20of%20Zero%20Tolerance%20for%20Female%20Genital%20Mutilation%20is,was%20first%20introduced%20in%202003.

- https://www.euronews.com/2021/02/06/fgm-covid-19-pandemic-thought-to-have-sparked-a-rise-in-female-genital-mutilations-say-exp?utm_source=flipboard.com&utm_campaign=feeds_news&utm_medium=referral

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WJwP6C5q6Qg

- https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/female-genital-mutilation

Siona Manocha, a senior, has attended Keystone School since kindergarten. Through The Keynote, Siona employs the use of visual art and media to highlight...

Ali Wu • Feb 12, 2021 at 5:05 pm

Why is this not trending?? ahem ahem